Tech Tips

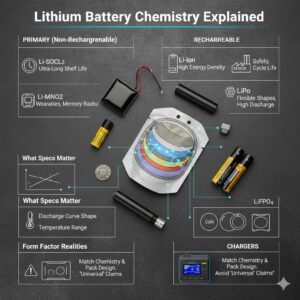

Lithium Battery Chemistry Explained for Product Teams and Technicians

When people say “lithium,” they often mean “small, light, powerful.” In engineering and field operations, that shortcut is how you end up with brownouts, swollen packs, premature failures, and support tickets that never stop. lithium batteries are not one product category. They are a family of chemistries with radically different behaviors, risks, and best-fit use cases.

If you build, deploy, repair, or resell hardware, you do not need a PhD in electrochemistry. You do need a clean mental model for what each lithium chemistry is good at, what it is bad at, and what specs actually predict success in the real world.

First principle: chemistry drives behavior, not the label

Two cells can share the same nominal voltage and similar capacity yet behave differently under load, temperature, and time. The chemistry affects:

- Discharge curve shape (flat vs sloped)

- Pulse capability (how it handles spikes)

- Shelf life and self-discharge

- Temperature performance

- Safety profile and charging requirements

- Whether it is primary (non-rechargeable) or rechargeable

Start selection by deciding if your product needs primary power (long shelf, low maintenance, often one-and-done) or rechargeable power (cycling, charging electronics, more complexity).

Primary lithium chemistries (non-rechargeable)

These are the workhorses for sensors, meters, alarms, and any device that must sit for years and still wake up reliably.

Li-SOCl₂ (Lithium Thionyl Chloride)

Where it shines: ultra-long shelf life, very low self-discharge, excellent energy density, strong low-drain performance.

Where it bites: poor tolerance for high pulse loads unless you use a hybrid or add a capacitor. Some devices need careful design to handle voltage behavior under bursts.

Best for: remote sensors, utility metering, asset tracking with infrequent transmissions, industrial monitoring.

Li-MnO₂ (Lithium Manganese Dioxide)

Where it shines: strong performance in coin cells and compact formats, good for moderate drains, widely used and predictable.

Where it bites: still not rechargeable, and burst demands can be a problem depending on cell design.

Best for: coin-cell applications, memory backup, small electronics, wearables that do not recharge.

Li-FeS₂ (Lithium Iron Disulfide, often AA form factor)

Where it shines: drop-in style for common consumer sizes, good power delivery, solid cold performance.

Where it bites: still primary, not designed for industrial “decade-long” deployments like Li-SOCl₂.

Best for: field gear that uses AA/AAA but benefits from lighter weight and better performance than alkaline.

Rechargeable lithium chemistries

If your device cycles daily, streams data often, or has motors, rechargeable becomes attractive. It also adds failure modes if charging is wrong.

Li-ion (typically NMC/NCA variants)

Where it shines: high energy density, good all-around choice, common supply.

Where it bites: requires a proper protection circuit and correct charging profile. Thermal management matters.

Best for: consumer electronics, tools, mobile devices, robotics with moderate to high draw.

LiFePO₄ (Lithium Iron Phosphate)

Where it shines: safer chemistry, strong cycle life, good for higher loads, stable behavior.

Where it bites: lower energy density, different nominal voltage profile than typical Li-ion.

Best for: industrial packs, stationary systems, applications where safety and lifespan beat maximum capacity.

LiPo (Lithium polymer, often pouch cells)

Where it shines: flexible shapes, high discharge capability variants exist, common in compact designs.

Where it bites: mechanical vulnerability (puncture risk), swelling concerns, requires careful charging and protection.

Best for: drones, compact devices, slim form-factor products.

What specs actually matter (and what is mostly marketing)

Nominal voltage is not enough

A device that “supports 3V” may still fail if it needs a flat discharge curve and you give it a chemistry that sags under bursts. Always consider minimum operating voltage under load, not at rest.

Capacity (mAh) does not predict burst performance

Burst-heavy devices fail on internal resistance and chemistry behavior. A slightly lower-capacity cell can outperform a “bigger” one if it handles pulses better.

Temperature range is a design constraint, not a nice-to-have

Cold can crush available capacity and voltage. Heat accelerates aging. Pick chemistry with realistic margins for your deployment environment.

Shelf life and self-discharge are operational costs

If you stock spares, shelf life matters. If you deploy devices for years, self-discharge matters even more. Primary lithium chemistries dominate here, but only when matched correctly to load profile.

Form factor and terminations are failure multipliers

Coin cells, cylindrical cells, and wired packs have different mechanical and electrical realities. A connector that “almost fits” is a guaranteed field failure later. Polarity mistakes are more common than people admit.

Form factor reality check: coin cells vs cylindrical vs packs

- Coin cells are great for ultra-low power electronics, RTC backup, and compact devices. They are not designed for repeated high bursts unless your circuit buffers power.

- Cylindrical cells are common in industrial and higher-capacity use, with better thermal and mechanical robustness.

- Wired packs introduce connector type, polarity, cable strain relief, and pack configuration (series/parallel). Treat them like a subsystem, not a commodity.

If you are sourcing online, prefer catalogs that let you filter by practical fields like voltage, chemistry, size, and capacity. That is not a “nice UI feature.” It is how you prevent misbuys at scale.

Chargers: where good batteries go to die

Rechargeable lithium is unforgiving about charging. A charger is not “just a charger.” It must match chemistry and pack design. Wrong charging profiles shorten life, create swelling, and can become a safety hazard.

If you are buying chargers alongside packs:

- Confirm chemistry compatibility and charge algorithm

- Verify connector polarity and fit

- Prefer protected packs or systems with proper BMS design

- Avoid vague “universal” claims unless you control the pack design and know what you are doing

Compliance, shipping, and traceability: boring stuff that saves you

For technical teams, the painful costs come from rework and uncertainty, not from unit price.

Look for:

- Clear labeling, consistent SKUs, and stable listings

- Traceability signals (date codes, batch consistency where available)

- Transparent return/replacement policy, because mistakes happen

- A supplier that acknowledges compliance and shipping constraints for batteries, instead of pretending they do not exist

If your procurement process does not capture what you ordered, from where, and when, you are setting yourself up for “random failures” that cannot be debugged.

A no-drama selection workflow you can standardize

Here is a simple workflow product teams and technicians can actually follow:

- Identify whether the device needs primary or rechargeable.

- Define load profile: steady low drain vs pulses.

- Lock the chemistry based on load and deployment duration.

- Match voltage behavior under load, not just nominal voltage.

- Choose form factor and termination that fits mechanically and electrically.

- If rechargeable, validate charger compatibility.

- Document the exact SKU and keep a reference list for reorders.

Do this consistently and battery sourcing stops being a guessing game. It becomes a controlled input to your reliability, RMA rate, and customer experience.